In the Studio: Nosaj Thing

In many ways, Jason Chung (a.k.a. Nosaj Thing) is an archetype for promising bedroom producers. […]

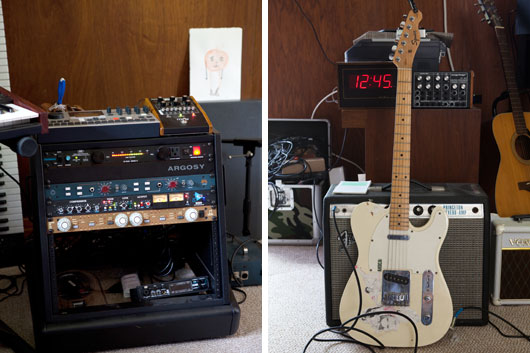

In many ways, Jason Chung (a.k.a. Nosaj Thing) is an archetype for promising bedroom producers. Like many, he began making tracks in his room as a teenager, initially piecing together hip-hop-inspired instrumentals in a room at his parents’ house before evolving his craft towards the more sophisticated electronic music that would eventually propel him to the forefront of LA’s beat scene and yield a pioneering debut LP, Drift. Somewhat unsurprisingly, Chung still prefers to produce in a simple home studio, which is now based in South Pasadena, just outside of LA proper. XLR8R recently payed Chung a visit to find out more about his current set-up, his ever-present interest in evolving music technology, and the process behind his forthcoming sophomore (and appropriately titled) LP, Home.

XLR8R: Have you always had a home studio?

Nosaj Thing: Yeah, pretty much. I think I would always want to keep it that way, because that’s where I feel most comfortable. I don’t want to dress up just to go make music.

And you started producing just in your bedroom?

Yeah, I was a freshman in high school—I think I was 13. I had some older friends that were into house music and one of them hooked me up with copies of Fruity Loops and Reason. At that time, I was actually more into DJing, but I did have a keyboard—a Roland JX-305 that was kind of hard to use. I grew up with computers, so it was a lot easier, especially visually, to use software [instead].

You have a lot of hardware now though, when did you start adding those pieces to your studio?

Right after high school, I got a job at a music store and tried to save up to get the gear I needed. After a while, I got an MPC—I was going to community college at the time and I got a grant which I just used to buy it on Craigslist. [laughs] I had always wanted an MPC since high school because of DJ Shadow, Prefuse 73, and DJ Krush, but once I got it, it wasn’t what I had expected it to be. I had different melodies and ideas in my head, and after starting out with software, it just seemed so slow; it felt like I was going backwards.

Was there anything you liked about it?

In some ways, I did really like it because the design was amazing and it was fun to not use software—it makes you think differently. Every piece of gear and every different software you use I think affects your music. I feel like a lot of different genres are inspired by the software [the producers] use. For example, I’ve noticed that a lot of the dudes who make trap beats use Fruity Loops, and that program’s whole UI is based around a 16-step sequencer. How would you not come up with hi-hat patterns like that when the whole program is based around the step sequencer? For me, the software I use, and even the colors of the program, affects the way my music comes out.

Now that you have both hardware and software, how do you strike a balance between the two? Is there a particular point where you transition from one to the other or are you working in both worlds all the time?

What inspires me most is just sound in general, so I usually start off with sound design—whether its hardware or software. I don’t think hardware is necessarily better than software or vice-versa; both are just so advanced now that whatever sounds good, you should just use. For me, I like to use a lot of software, because it’s convenient and the workflow has gotten so fast that there’s nothing that interrupts your process. I was thinking about this recently, especially with all the new iPad apps, and I think that gap between having your idea and getting it out is more transparent now. The more the tools develop, I’m not thinking about things in technical terms [anymore].

You’re mostly an Ableton user now? When did you start using that program?

I started messing with Ableton in 2003—I just had a demo version. I mainly used it for time-stretching, and I would use it more as a separate tool than a DAW. I was drawn to the interface—it was so different [than the other programs at the time]. Ableton is really mindful of its aesthetics and for some reason I was really drawn to that. I had used Logic to write the first EP and at the same time I was using Ableton to perform, and as Live developed, I was getting tired of bouncing all my stems from Logic to Ableton. Ableton seemed to be focusing more on creation than just sound. I was really drawn to that and switched over right when I began writing the first album.

How involved are your Ableton sessions? Do you automate a lot and get very detailed with the software?

I don’t really do too much automating—I’ll do that all at the end, just minor tweaks—and I don’t even really use EQ, actually. I rarely EQ.

What about filters?

Yeah, I tend to use filters instead. I just like starting out with a certain sound palette and then finding sounds to fill certain gaps.

So you don’t just try to build the song by musical components. Is it more based on filling in the spectrum of sound?

I see it visually. If I start out with a pad, I see it in the middle of the spectrum, and then I fill those gaps left in the rest of the spectrum.

Is that an approach which developed over time, or is that the way you’ve always seen music while producing?

I feel like I was always gravitating towards that technique, and then once people were hearing and commenting on my mixes, that’s when I noticed it. I think that’s the beauty of electronic music—you have full control of every sound. If you have a kick drum that needs to be a lower or higher frequency, you can easily make that change. You’re not working with the same rules as traditional instruments.

The “Eclipse/Blue” single features a vocalist. Are there more vocal collaborations on the new record?

There are a couple more. Elin Kastlander from jj did some stuff, more background vocals, for a couple of songs, and there’s a song with Toro Y Moi too.

Was incorporating vocals into your work a challenge?

Yeah. Once you bring vocals into the mix, the whole focus of the song changes. It was a challenge to mix as well as arrange, but it was something I’d been wanting to do for a while. Right now, I’m still learning, but I hope to do more of it. I did get really lucky with this record and all the vocal sessions went very smoothly. With Kazu [of Blonde Redhead href=”http://www.facebook.com/blonderedheadofficial”], we recorded her vocals over one full day. I was in New York, and we got to record her vocals at Electric Lady Studios [originally Jimmy Hendrix’s studio], and we were able to knock it out in one session. She sent her vocals to a friend of hers, Drew Brown—who engineers for Radiohead—and he did the vocal processing on the song and really brought it to life.

You’ve been a home-based solo producer for a long time now, how do you keep things fresh?

What really helps me is just experimenting. Once you feel like you have a certain routine, [you have to] change that up. Sometimes I’ll get in routines and I’ll have a system and it will start getting boring, I’ll just make the same type of song everyday. That’s when I get the reality check and I’ll change the tempo, change how I start the songs, or something like that. That’s how I’ve learned and come up with new tricks—you have to try new plug-ins, flip the snare and kick around, or reverse your usual chord progression. That’s how I stay inspired.