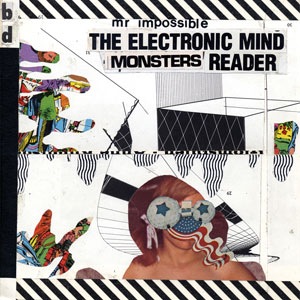

Black Dice Mr. Impossible

Dusting off old Black Dice records (or just typing the band’s name into an iTunes’ […]

Dusting off old Black Dice records (or just typing the band’s name into an iTunes’ search box) reveals a sonic journey completely distinct from that of any of other recording artist. The music is difficult, of course, and, at times, confoundingly strange and different. Most artists are so far afield from Black Dice’s tense and dissonant noise that it can be hard to even call them music by comparison. The group has also undergone great changes in sound and style from record to record, as if its members are playing devil’s advocate with themselves and the larger music community. After all, why sound like somebody else when it’s been done before? Why recycle old ideas when you can come up with something totally new and different? Black Dice’s latest effort, Mr. Impossible, adds another chapter to the now-trio’s long, strange trip, with what might be its most straightforward album yet.

In the world of Black Dice, however, straightforward doesn’t mean what it does elsewhere—all we can say about Mr. Impossible‘s tracks is that they are song-like, its melodies are apparent, and, occasionally, patterns and structures emerge. Those may seem like obvious descriptors for any recorded music, but Black Dice has never thought of traits like organization, repetition, and tonality as required elements in their work. On this record, they appear to be using them only as a subversive medium through which to share their surreal, noisy soundcraft. The first half is heavy and uptempo, most obviously comparable to rock acts like Health and Battles. Yes, the album was made with computers, drum machines, and synthesizers, but apart from the instrumentation, it bears virtually no resemblance to dance or mainstream electronic music whatsoever.

“Pinball Wizard” launches off with a churning drum track and a pair of oddly harmonized guitar-sounding riffs, which play off one another before a quasi-vocal melody begins warbling over the composition. Vocal noises are a major presence on Mr. Impossible, but instead of making songs more relatable or participatory, as they would in most other forms of music, the wordless and heavily processed vocals have a disorienting effect. “Rodriguez” and “The Jacka” continue with similar sonic themes, both using essentially the same rhythmic and melodic motifs, albeit with their own chaotic flourishes. “Pigs,” a fiercely tumultuous piece of pseudo-punk, serves as the record’s climax, not to mention its most energetic and accessible track, especially for those not familiar with the group. After “Pigs,” Mr. Impossible drops abruptly in tempo and energy, moving away from the frenetic rambunctiousness of the first half. The hardcore-punk attitude fades away, with the remaining five songs more closely resembling the early, artsy electronics of fellow New Yorkers Animal Collective and Gang Gang Dance. “Spy vs. Spy” takes cues from the plethora of artists still producing spacey, leftfield hip-hop, and the record continues to peter out with a smattering of oddball synth jams and dubby electronics until “Brunswick Sludge (Meets Frontrange Tripper)” fades its consonant melody and live-sounding drums into noodling synth notes across the song’s six minutes.

Mr. Impossible is definitely a weird record, much stranger and intentionally iconoclast than those coming from any of Black Dice’s peers. Still, it is much less difficult than the running average of Black Dice releases, even if it’s not exactly a casual listen. It’s a record either for the distant background or careful examination (or just those accustomed to the avant garde and experimental); it’s the antithesis of a comfort record; it’s the bane of those seeking familiarity and convenience, but it is not avant garde itself, as it lacks an innovative or fresh quality that might make it more influential or cutting-edge. For those interested in zany experimentalism, Black Dice’s latest is a welcome addition to a long line of solid releases, but for those who have never been awed by this brand of cacophony, Mr. Impossible offers little besides noise.