In the Studio: Tycho

For much of the past decade, Scott Hansen has been piling up accolades as an […]

For much of the past decade, Scott Hansen has been piling up accolades as an artist. But prior to last year, it’s fair to say that he was often thought of as an amazing graphic designer who also happened to make some nice tunes under the name Tycho. In 2012, following the widespread acclaim surrounding Dive, his most recent full-length, Hansen’s musical chops have moved to the forefront, and it’s likely that a certain portion of Tycho fans now know a lot more about his songs than his design work. Questions of perception aside, there’s little doubt that the San Francisco-based Hansen is an incredibly talented individual. But given that the recent spotlight has shifted toward his musical output, we figured now would be a good time to delve into Tycho’s studio and find out a little more about exactly how he creates his rich, synth-laden soundscapes.

XLR8R’s In the Studio series is sponsored by Dubspot.

Has your production method evolved much over the years?

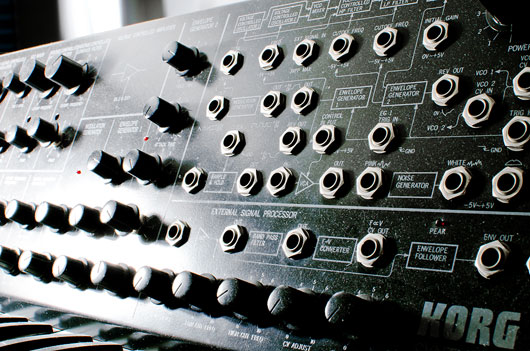

No, I’ve pretty much always had the same process. It’s always been hardware. Actually, when I started out [in 2001], I’m sure there were some people doing stuff with computers, but there weren’t really virtual effects and virtual synths and all that. All my initial gear was outboard and I did all the sequencing and recording outboard too. Basically, I didn’t use the computer for anything. I started using the computer in a limited sense for The Sunrise Projector (Past Is Prologue). Now, everything is outboard except for the arrangement, and that’s all done in Reaper. Actually, not everything. I definitely use quite a bit of compression and EQ plugins. The effects I’m using are for color and to try to get the vibe of the unit. I’ll use outboard stuff, and then I’ll do the technical/surgical stuff in the box.

You’re pretty heavily analog in terms of the sounds and equipment you favor.

As far as tone generation, it’s all either analog or virtual analog. It’s mostly outboard. I just feel like no matter what is generating the tone, if it goes through all the transformers and circuitry of analog hardware to get it into the box, that’s where I feel like it adds that kind of magic. And if you have an analog synth to begin with, there’s a little bit more.

When did you start collecting gear and synths?

When I started, the first thing I got was a drum machine and a little synth. I moved up to a sampler/drum machine, the Ensoniq ASR-X Pro. I just started [collecting gear] after that. I think my first real synth was the Korg Triton. It’s a workstation. I got it because it could also do sampling and sequencing, so I knew that I could use that instead of a computer. Then I learned about analog. I really didn’t understand the difference between analog and digital and virtual analog and all that. I got a Korg Mono/Poly, and that’s when I realized what everyone was talking about. That was right when people were figuring out that the old synths were kind of better, anyways.

Would you say that you have a gear fetish?

I like tweaking the studio and wiring things up almost as much as making music, so that’s kind of a hobby of mine, in and of itself. I don’t like to collect gear that I know I’m not going to use, though. I don’t like the idea of unused gear laying around. Right now, I think I’m kind of in that spot inadvertently, just because there isn’t enough to space to have everything always hooked up. I’m trying to keep it slimmed down, so I keep the ones that I’m really using at the moment here, and the rest of the stuff is all stored away.

Do you have a favorite or most essential piece of gear?

Absolutely. I feel like I think about that a lot. I don’t like the idea of being tied down by all this [equipment]. I really love the idea of just being able to go with a laptop, but with my process, it’s not really possible, so I kind of fantasize about what I would take. I think it would be the Mono/Poly and a Virus Indigo. If I had those two, and maybe my little Sequential Circuits, I could probably get away with it. Then I’d probably bring a little rackmount Moog. Also, my preamps and compressors, I would definitely need that. It wouldn’t be light, but I could probably get away with just a set of favorite stuff.

How do you make such a rich, warm sound?

I think it’s an artifact of several levels of effecting. You’ve got a synth, and you’ve got a pretty warm tone to begin with, and then I’ll hit an analog delay. That will impart its own character. I use my Roland Space Echo a lot, because it’s tape, so you get the tape saturation and warmth. And then you run it into the preamps, and those are transformer based, which gives its own kind of harmonic distortion. Then I’ve got these things called Distressors, they’re these Swiss-Army-knife-type compressors. They’re kind of tape-saturation emulators, so that’s another layer of tape and harmonic distortion. Usually, after that, I go into the box, and there are a few techniques to warm things up or give [the tones] this rich sound. [Those techniques are] usually convolution reverbs and delays, things like that.

Did you have formal music training or are you self-taught?

When I was 22, I just started messing around with drum machines and approached it from a producing standpoint. Slowly, over time, I learned enough that I started considering myself a musician, where I actually knew how to play instruments. But still, when I talk to my real musician friends, they’re calling chords out and I have no idea what they’re talking about. It’s more about playing by feel [for me].

You do incorporate some organic instrumentation though.

Yeah. As synth driven as Dive is, if you really break it down into percentages, it has quite a bit of sampled drums. Almost all the songs were either originally written on guitar or feature a guitar in them. Almost all the basslines are normal electric bass.

How do you go about melding traditional/organic instrumentation with electronic music without it sounding forced?

That’s never been that difficult. I think it’s because I use so many effects on everything. At the end of it, sometimes the guitars end up sounding indistinguishable from a synth. Once you put enough reverb, compression, and delay on things, you can start to get things into the same space, no matter where the original tone came from. Basically, I’m kind of applying the same ideas to all the sources, so at the end of it, it becomes cohesive.

Do you have a set songwriting process?

It’s almost always melodic, like [I start with] a 16-bar melody. Usually, I immediately throw in the bass. Those are the important parts for me to set the mood of a song. The melody has this one-dimensional thing going on, and then you throw the bass in and it can open it up and change things. From there, I start working through all the strings. For percussion, I’ll usually start with some [kind of template], just a loop to give myself an idea or a grid. That’s the last thing I do, go in with a fine-tooth comb and arrange the beats to serve the music.

How much does graphic design play into your music-making process?

I drew my whole life, and then I found out about computers in college and what they could do—[before that], I didn’t really understand what design was. I started working on design, but I knew there was some missing piece. I feel like music and design complete the idea of each other for me. So, it’s like whatever I’m trying to express in one really can’t be fully expressed without the other. I’ve always seen them as the flipside of a coin and bounced back and forth. That’s the whole idea behind the music and really the design. I feel like my whole design career has been built up creating these storyboards for what will eventually be motion. That’s the next phase. I want to take the visuals to another place, where it’s taking that vision and fully fleshing it out. I see motion and sound as very related, so that’s the final thing. I feel like all the design has been little ideas and things to choose from for what will become a film-type thing.

Tycho’s Dive is out now on Ghostly.