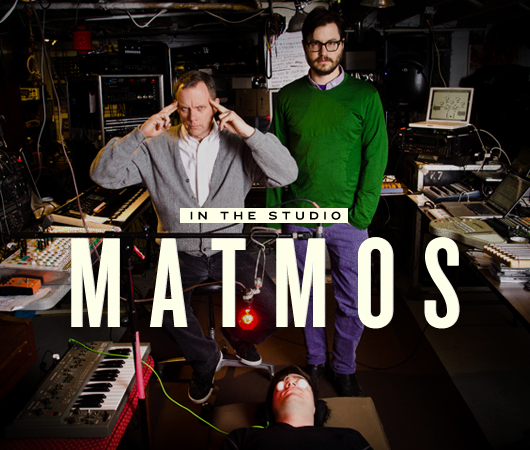

In the Studio: Matmos

Drew Daniel and Martin Schmidt, who together form the group Matmos, have spent most of […]

Drew Daniel and Martin Schmidt, who together form the group Matmos, have spent most of their production career seeking out unconvential concepts and sound sources to use within their adventerous electronic works, resulting in a discography that is rarely stale and consistently unique. For their latest record, The Marriage of True Minds, Daniel and Schmidt enlisted volunteers to participate in the Ganzfeld experiment, in which Daniel would attempt to telepathicly transmit the sound of Matmos’ then-unmade record to the participants, whose descriptions of what they heard in their head would in turn serve as the blueprint for the album’s tracks. In the process, subjects reported back everything from sloshing buckets of water to the sound of triangles and synthetic strings, leading Matmos to incorporate a wide range of unexpected elements while making their record. In order to gain some insight into exactly how it all worked, we visited Daniel and Schmidt in their basement studio in Baltimore—the duo’s adopted hometown since relocating from San Francisco six years ago—and picked the veteran sonic adventurers’ brains about their unconventional process and quirky set of tools.

XLR8R: Is this basement studio the biggest studio space you guys have ever had?

Drew Daniel: Totally. We have a baby grand piano and can set up a full drum kit, guitars, a bass, amps, and still have enough space for tons of keyboards. The amount of real estate is fucking awesome and it does change the way you work; you’re just more likely to try out a weird signal chain.

How do you guys connect all your pieces together? Does every unit correspond to a channel on the board or are you always changing how the signals are chained together?

DD: The patchbay gets a lot of work because we’re tracking and mixing through that mixer; we don’t like to mix on-screen. Our set-up definitely has to be flexible for lots of different projects, lots of different sizes of ensembles.

So you’ll use the computer as a platform to record and then run the audio back out through the mixer when you do mixdowns?

DD: Yeah, exactly.

And then you record the stereo mix back in the computer?

Martin Schmidt: Honestly, until very recently, we would record it onto DAT [tape]. But I don’t even know where to buy DAT tape in bulk in Baltimore.

DD: DAT is so exotic now, it’s like saying you archive to wax cylinders or something.

How recently did you make the switch?

MS: In the last year.

DD: It was just that we know the old ways and it’s what we’re comfortable with. I don’t like to mix on-screen; I like to use my hands and fingers and to touch an EQ or a fader, and Martin is the same way. And I think there’s something nice about the material feeling of committing to tape—you’re actually taking up material space in the world.

MS: It has a practical aspect as well. It ties in with a fear I have for everyone—especially younger people—in the musical world, which is that I have records that I bought in high school in 1981, and I just sincerely doubt that in 36 years, these kids are going to have the files they downloaded in high school. The practicality of DAT is that I like to have the stuff on the shelf. Those DAT tapes are not going to crash.

DD: There’s a weird sweetness to opening up a cigar box and there’s a DAT with our handwriting from 1995, and there they are, our first songs. To be able to go back like that is fun. On the other hand, of course I like the speed and transparency of a digital mix that is then uploaded and that can then be checked out by someone in Paris who wants to hear it; and it all happens without licking a stamp. We definitely see the appeal of the modern world, to a point. [laughs]

Do you guys have set roles or a specific way you split up the work when producing together?

MS: Drew is a much more obsessive fiddler—he’ll do something, go back, change it, go back change it, and so on. I learned how to do stuff on tape and I’ve retained those habits. I still think about tracks as if they were on tape in a way.

DD: Martin is more likely to sit and tinker with a synthesizer sound until he’s got something that he is really happy with and then record it. I’m more likely to sit in Ableton and chop up samples and build rhythmic kits or try out a plug-in. We just work in slightly different ways, which is good because we don’t step on each other’s toes as much. There are parts of the process that are more me or more him. Martin mixes our records. I don’t. I had a sinus infection, which caused me to lose a lot of hearing in my left ear above 12 kHz. I don’t trust my hearing as much as I trust Martin’s, so he mixes us because he’s more of a stickler and he’s much more precise. I’m more likely to laboriously make 20 different hi-hat patterns and then have Martin decide which one we should use.

You guys have some really unique pieces, such as this wooden synth that looks kind of like a xylophone. What is that?

DD: It’s called a Sidrassi Organ. It uses piezo [microphones] that convert pressure into pitch and CV information and then it has some really complex LFOs that seem to drive the left-right panning. It’s one of the most actively stereo-electronic instruments I’ve ever played. It’s a wildly unique piece of gear. It seems to have buttons that short-circuit and randomize lots of its values, so you really never get the same effect with that thing.

MS: It’s an instrument designed by Peter Blasser.

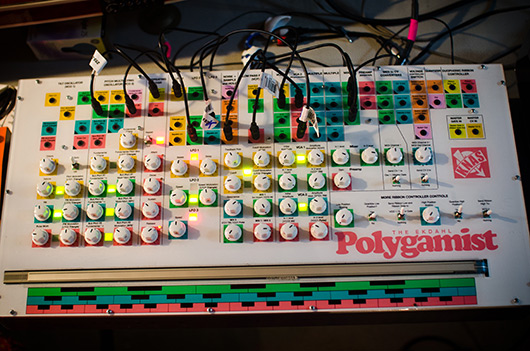

You also have a Polygamist synth, which I’ve never seen before. What’s the story behind that?

MS: It’s the only one in the world at this point.

Really?

MS: Yes, I work in a record store in Baltimore, The True Vine. One day this kid came in—giant, liberty-spikes mohawk, looks like a punker from 1983—and he saw that we had an extra room and asked if he could set up a shop where he would fix amps, and synthesizers, and stuff. So we said, “Hell yes,” and after a few months of doing that, it became clear that he was capable of doing a lot more than fixing stuff. I asked him if he could build something from scratch and that was the beginning of building the Mosturizer synth, of which we’ve sold 500 now. He now makes his living off of building these things and the Polygamist is the next big project that we’ve come up with together. I’m no solderer, but I am an evil capitalist, or something, so I put in the money. [laughs] And he’ll listen to me when it comes to interface design and graphic design at times, although he has some really strong opinions.

Most of your records are guided by conceptual themes in some way. For this one, you had people participate in the Ganzfeld Experiment, and then used what the participants had described as the guide for creating the album’s songs. What exactly is happening in the period between gathering this material and then actually producing the music?

DD: Every record is different. For this [one], we did a lot of telepathic experiments at home in Baltimore and abroad in Oxford and Pennsylvania. We spent a couple of years in research mode, making kind of spooky, occult pieces out of the sessions, but not making songs in the way that we knew that we were going to.

In that period are you not making music then?

MS: Oh, God no. It’s not as serious as that sounds.

DD: Martin is always playing and improvising with lots of other people and I have my side projects and other things I work on. But it is true that when it’s time to go, “Okay, is this a song for the telepathy record?” and the answer is “No,” or “Not strongly enough,” then we have to keep working. The concepts do impose a certain expectation.

MS: Honestly, it’s freeing, that’s the truth. You don’t start by sitting down and saying to yourself, “What am I going to do?” and then start a beat and then fiddle something on top of it and then fiddle something on top of that—you can end up making a lot of stupid techno that way. So this gives us a new shape of skeleton every time and leads us to places we wouldn’t necessarily ever go to if we didn’t have these [guidelines].

There are a lot of sounds on this LP—and most of your albums—that are not traditionally musical. How do you go about recording and capturing those?

DD: Usually we’ll start by trying to do it ourselves in our studio. Martin is generally the engineer and player of objects, and I have a portable Zoom recording device and whenever there is something that might be noteworthy—whether it’s crows freaking out in the trees next to our house or humans freaking out, like after the Ravens won the Superbowl—I’ll whip that out and try to gather things from the real world. We try to avoid preset sounds of FX from a collection unless there is some conceptual reason to go there.

How do you approach mixing those sounds into the tracks? Do you sort of treat them as if they were musical instruments?

MS: It’s different with every song, but I definitely am guilty of reducing everything in my mind to a kick drum, a hi-hat, a horn line, a bass—I think I do it fairly transparently now, kind of without really thinking about it. It almost seems a bit boring to work with those actual things now. Yes, there is an endless micro-variety between different kick drums, but once you’ve sourced kick drums from everything in the world, actually banging a beater on a drum seems a little dull.

DD: It’s the same with how we edit and arrange audio, too. The way that I might crop or edit a sample, I may have in mind the vocabulary of a snare or a hi-hat. There are ways to edit the noise of somebody pulling their clothes out of a gym locker where you can turn it into a sound that’s closer to a woodwind instrument or something. We try to treat these noises as if they were already musical instruments.