From Studio to Stage: Matias Aguayo

Though our conversation with Matias Aguayo has been officially filed into our From Studio to […]

Though our conversation with Matias Aguayo has been officially filed into our From Studio to Stage series of interviews, it might more accurately fall under the title “From Stage to Studio and Back.” As the seasoned producer/DJ explains, his creative process is very much tied into his DJ sets and live performances, during which he experiments and develops his songs in an improvisatory manner, testing and twisting them in front of audiences many times before ever recording a note. Now, with the Chilean-born artist gearing up for a newly reimagined live show—which enlists the help of Alejandro Paz, a regular on his Cómeme label—we paid a visit to Aguayo’s Berlin studio to find out how he manages to fluidly move his productions between both the performance and studio spheres. The space—which features a view of a graveyard from its windows—is located in the back of an old warehouse and has been dubbed “District Union” by Aguayo and his Cómeme compatriots. In the process of showing us around the place, the producer also touches on the collaborative and improvisatory spirit which fed his new album, The Visitor, and discusses how he and Paz have found ways to continue developing the music together as performers.

XLR8R: In conjunction with the release of The Visitor, you’re launching a new version of your live set. Could you take us through the basics of your set-up?

Matias Aguayo: Yes, and there we get right to the center point of the “studio to stage” idea. I think in my case, the relationship between studio and stage is often the other way around. If we’re talking about the ways we are recording and developing music in the studio, I think it’s as important to talk about going from the stage to the studio. I like to develop my music while I play, and then to later record it. In the case of The Visitor, I had already developed many of the tracks while playing rhythms that I had taken with me, and then improvising [on top of them] in the clubs. That is how I developed my singing and the structure of the tracks, and then I would bring those ideas to the studio. I see a danger in it being just one way, from studio to stage. Obviously, it is different to sit in the studio and imagine what might happen on a stage. I prefer to develop the music really where I will need it later on. I think this is important to explaining the whole concept of my studio, actually. It is not simply an end of things, but actually part of a bigger plan.

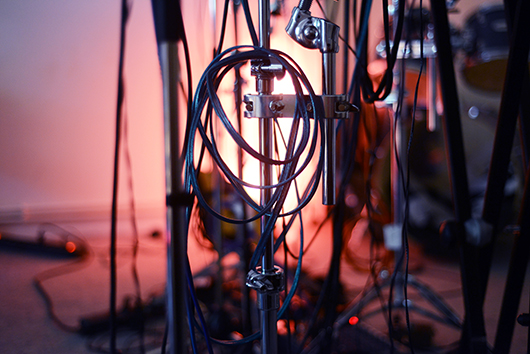

When I built this studio, my main idea—which I conceived very much in collaboration with Philipp Gorbachev and also with Scott Monteith [a .k.a. Deadbeat href=”https://soundcloud.com/deadbeat”] later on—was to have a studio that wasn’t just for mixdown. I didn’t want mixing and music production to be linked so strongly together as it is in the accepted sense of an electronic-music studio, where there is a computer in the middle of a desk, a lot of machines connected to this computer, and some speakers around it. I wanted to get away from this “office” feeling, and have something that was a sort of recording/rehearsal space. That is why, in this studio, there is no place to sit, everyone is standing. [In this space,] Philipp [Gorbachev] and I built what we call a “satellite system”—tables and stands with different instruments on them and formed almost in a circle, so as to have a place where you can really play things out. I wanted to avoid being exclusively in front of the computer screen, and instead spend more of my time actually playing stuff and getting back to the idea of being a “musician” who strives for the perfect take, rather than just recording some bits and bops and immediately editing them together on the screen. I try to avoid the computer screen because screens are following us in the form of smart phones and laptops, and we are all the time looking at these screens which translate our music as something that merely goes from left to right. I believe that music doesn’t just move from left to right—it’s more complex than that.

What sorts of equipment are you using in this “satellite system”?

I think what is important to note is that there is not one big mixer, but instead several small mixers that connect the stations. Some of the main components of the current set-up are the Vermona drum synth [DRM1 MKIII] and a Tube Tech CL1B compressor (which is a very important part of the recording chain), a Brauner microphone (also for recording), a Sennheiser MD 441 [microphone], and for other things just the classic Shure SM58 and SM57 microphones. There are a lot of little machines as well, such as the Oberheim SEM synth and an 808 imitator called the 522 by the German brand MFB.

I also use a lot of machines that many people would likely consider toys, like an old Yamaha digital drum pad from the ’80s, which is really nothing spectacular. I also like preset sounds. I don’t consider myself much of a sound designer, so I prefer working with machines that are somewhat limited. I don’t like to get too deep [into programming]. I also have a newer Yamaha drum pad called a DTX, which is very nice to play with your hands. When I look for instruments now, I am looking for pieces that have a nice sensitivity. I do use electronic sequencers and quantizing as well, but for all these more modern Latin rhythms, I can’t program them, so I have to play them. There is a certain kind of shuffle between hits and strange syncopations that I haven’t been able to generate with any sequencer. For me, its very important to have instruments that I can play. Also, when I DJ, I use the E&S DJR400 mixer, and at some point I realized I liked the sound so much that I began running drum machines and FX through it, using the E&S to equalize and filter the signal. There’s a pedal company called Snazzy FX that makes psychedelic pedals, and I really like their analog delay, the Wow and Flutter; it’s a very nice, slightly distorted delay that feels very organic.

Do you avoid using a computer in your live performance?

Live, we use the Korg Microsampler, which allows us to avoid using the computer on stage. Again, it is the same thing; I open my computer for trying to answer too many emails, writing text, or reading the news, so then I don’t want that to be the machine that I open again once I’m in the club. It wouldn’t really feel like the club, it would just feel like an office. I can import certain loops and play certain things from the Microsampler instead of needing a laptop. It’s very important to our live set-up. There is also a very interesting MIDI controller I use as well, the SND ACME-4. I don’t use much MIDI, but I wanted a machine that could act as a stable MIDI clock and also allow me to add a precise amount of swing.

How did you come across all these units?

This particular combination came about because of the album work. Some of it is a bit older and some is a bit newer, but most of them come from the period after I had finished Ay Ay Ay. On that record, I worked mainly with vocals, so my main instrument was my voice and a microphone. A lot of the gear [I have now] was bought in recent years, with the goal of becoming part of this playful studio and to fit into the idea of this space being a studio/rehearsal space, especially for jamming. I like to keep it very atmospheric in here, there’s a low light and the windows open to a graveyard. It’s a special atmosphere in here, and I think it’s a very inspiring atmosphere to play and jam.

When you were developing the songs outside of the studio, were you bringing this whole set-up with you to gigs?

No, not at all. I had a set of rhythm [tracks] that I was always working on, and I would take them with me to DJ gigs. When I DJ, I use CDJs, and I’ll work the rhythms into my set and then sing, and play percussion on top using a few small instruments I have with me in the DJ booth. This is how I developed many, but not all, of the tracks on The Visitor. For me, it was really important to have songs on the album that I could really play out live.

If you develop a vocal line in the studio and you are sitting, it’s cozy, and that will make you sing a certain way—maybe you’ll use a deeper register or sing quieter because the volume of your voice doesn’t really matter. In a club situation, where you can have feedback problems and so on, you need your voice to be strong. Then, when you improvise, you automatically begin in a register where you are especially strong and that is the best for a live situation. This makes the development of the song much different than in the studio. I also like to record full takes, and I can do that because I rehearse the melodies and vocal lines many times live before going into the studio. It can still be challenging to do do single takes, especially because I know that I could just cut up the tracks and take certain parts, but I think it makes for better musicianship when you take the time to learn the song and then record it. It’s much more fun that way too.

When you begin the recording process, are you still improvising then?

Yes, I leave a lot of space for improvisation, of course. There was a lot of jamming that led to the tracks on the album, especially with Philipp Gorbachev and Alejandro Paz, who plays with me in the live show. Those jams were very much about recording a lot of improvisations until we found a loop or an idea that was the “perfect” one. I like the idea of continuing to play and perfect something [over and over] because you find these slight variations, and it can be really fun. Improvisation is an essential part of it, everything on the record comes from improvisation.

And now that the record is done, and you’ll be playing these completed songs to an audience, how do you make space for improvisation?

To me, it feels really pointless to just play the rhythm tracks of the album and then just play a few things with Alejandro [Paz] on top. It is much more fun and much more exciting to do something else [instead], so we have now built a live performance which is developable—there are many parts in each song that are left open in order to improvise, but we have an idea of what direction we will go in. During the touring, we can become better and better at it and learn more what does and doesn’t work. It’s sort of like gardening, in the sense that we know what seeds we are going to use, and what earth we are going to plant [them in], but we don’t know exactly how it will come together. We’ve tried to achieve an electronic set-up that still allows us to play very freely.

Do you and Alejandro have specific instruments or roles within the live set?

I mainly sing and play synthesizer, and I’ll also play a little drum machine and do percussion with the Vermona drum synth and a few other little things. Alejandro plays the Korg Microsampler and the electric guitar, and helps me make a wall of sound by sometimes just doubling the melodic lines I’m playing on the synths or singing. Our units are synced via MIDI clock, though sometimes we don’t use the clock at all. A big focus of the set is, of course, the singing, so Alejandro does a lot of backing vocals too, sometimes to almost act as my reverb.

How do you control the dynamics of a performance, especially when you are improvising?

That depends very much on the situation in which you are playing. I’m generalizing a bit, but if you are playing a more intimate space—a very small club where you have a lot of time to develop something—then you can really start from zero and let the music take shape over a long period of time; [you can] really warm up the situation and take the people somewhere. When you have less time and you are part of a bigger bill or a festival, I think the introduction has to be very strong. What I like to do is to start a show like that by just singing. I do that quite often when it is a shorter set. As a DJ, when you can sometimes play four-hour sets, it gives you a lot of time to develop something, but with a one-hour live show, I really like to get on stage and just sing without any backing track or beat [to start], and then I can loop the voice and sing on top of that. It allows you to begin from zero in a way, but still make a very strong gesture. Starting with my voice at full volume and just going “Da! Da! Da!” has proven to be really effective. [laughs]

The miracle of a microphone on a stage presents the best opportunity to get in touch with the audience, to get their attention and create a dialog. It helps to open them up to music that is maybe not so easily accessible. I think my music would be more difficult for an audience [to get into] if I were to just get on a stage, put on a record, and press play. But when I have a microphone and people can see that I am developing something with my voice, it automatically makes it so they can see the music being generated at the same time as they hear it. That is a very essential experience for a live audience. I think it’s also really important to have a strong ending. I have always thought that the beginning and the end are the most important parts of a performance, the impression the rest [of the performance] makes really depends on that.

Is there a particular action or feeling that makes for a strong ending in your opinion?

Of course it depends on the night, but what I really like to do is to have an ending that is strong but still keeps you wishing for more. I’d like the audience to get to the end and think, “Oh shit, I want to hear that again!”