In the Studio: Delorean

It’s been three years since we last heard from Delorean, the Barcelona group whose deeply […]

It’s been three years since we last heard from Delorean, the Barcelona group whose deeply melodic, richly textured 2010 album Subiza went over well among club and indie/pop audiences alike. (We certainly liked it here it XLR8R, as we named the LP our favorite release of the year.) After a great deal of work in its hometown studio and at Gigantic Studios in New York, the band has finished a new full-length, Apar, an alternately bright and wistful record that both broadens Delorean’s palette and presents its sound with a new, crystalline studio sheen that suits the music nicely. We spoke with singer and bass player Ekhi Lopetegi about the band’s studio, as well as how the group went about recording this new album in comparison to the last one.

XLR8R: Tell us a bit about the studio. Is it where you practice and record? Is it in Barcelona?

Ekhi Lopetegi: The studio is in Barcelona in this neighborhood called Poblenou, in this industrial area, and it’s actually shared with some other bands. There are four different rooms, and one common room that we all share for live performances. It’s pretty cool honestly—we have our production room and the live room, so we can both do production and rehearse when we need. And if we need to record something, we can also use the live room. Besides that, all of us come here to work… it’s like a workplace.

So you practice there, and you record there? And you write your music there?

Yeah. Although we all have computers at home, and sometimes we do our stuff by ourselves in our apartments. But it all got centralized here.

Have you been in this studio for a while?

We already had this room when we were doing the Subiza album, but we never used it as an actual studio. There wasn’t enough equipment. We didn’t have the mixing board that we have now, and we didn’t have the computer, the tape recorder, all the synths, and the hardware that we’ve been buying. So it was basically this room, but it was empty—it was probably just a laptop and some speakers. Now it’s a proper studio.

One gets the impression that the process for this record was much different than the one for the last one. Tell us a bit about how the songwriting worked for this new album.

I think [the songwriting] has changed, but not that much. We wanted to write the record differently, and instead of writing the record by clicking on the mouse and editing sound, we wanted to have actual instruments and mics and hardware, just in case. If we needed a hi-hat, instead of using audio samples, we wanted to be ready to actually play a hi-hat pattern, record it, and integrate it in the song. We wanted to have all these instruments ready, just in case we needed them to write the songs. We wanted to have the guitar ready to play and record, we wanted to have the bass ready to use, and we wanted to have drum machines ready to be used. But in the end, you end up working with a computer, editing sound and stuff, because it’s so easy. Even if we wanted to write the album differently, we kind of ended up going halfway to what we ideally thought the [recording process] was going to be.

What did you originally envision recording was going to be like?

I personally thought that the writing was going to be more like composition—you know, having a guitar and playing chords, or playing around with the drum machine a little bit and then recording it. In the end, we used hardware, but we still based the writing on the computer. But, you know, I played bass more than ever, there are more guitars than ever, and we had the drum machines ready in case we needed them.

It looks like you have at least three different Roland drum machines.

There’s the MicroComposer MC-202, and then there’s the Roland 707 and 727. We have a Roland 626 too. Those drum machines were bought because we were using the sound samples a lot. We didn’t want to do the drum patterns on MIDI, so we bought the actual drum machines. Some of the patterns and sounds are taken straight from the drum machines—not all of them, but they were there when we needed. There’s a lot of 707 drum snare on the record. A lot of drum snares that you can hear will probably be the [live] drums that we recorded or the 707. Some of the [707] snares were replaced by actual snares, but it was there.

We used to use a lot of the Korg Polysix plug-in, and we were using the Korg M1 plug-in too. But we didn’t want to use the plug-ins anymore, so we bought a Polysix and a M1. We also bought this Novation drum machine, which is like an emulation of the 909 and 808. So we pretty much have the 606, 626, 707, 727, 808, and 909.

Then we bought all of the guitars and basses. When we went to Chris Zane’s studio [Gigantic Studios in New York], we didn’t want to lose time with a performance—we didn’t want to spend a lot of time trying to record a proper bass or guitar performance. So we recorded all of the guitars and basses here using this old Studer mixing board. Everything was recorded here with no effects, and then we went to New York and re-amped everything, and that’s when we worked on the sound.

Were you using mostly analog gear for recording?

Not all of the stuff was analog. For instance, there’s this nylon guitar sound throughout the whole record that was taken from the Korg M1 plug-in. We tried to find that one on the actual M1 keyboard, but apparently that sound is only on the plug-in. They designed this sound exclusively for the plug-in, it’s called a “silk guitar” or something like that. All of those Indian/Arabic-sounding nylon guitar sounds are actually that synth plug-in.

For this new album, Apar, did you use live vocals for the female backups?

Yeah. There are two things: on one hand, we wanted to have female backups, to enrich the vocals, and on the other hand, one of the techniques that we used for writing songs and melodies was editing female voice audio samples. A lot of the sample-based vocals were actually sung by real singers. We wrote down some lyrics, and we worked with Cameron Mesirow [Glasser] and Caroline Polachek from Chairlift.

Basically, there were vocal samples that we wanted to be real. We would go with a sample vocal, write down a lyric for that, and try to emulate that with the [real] voice. We would adapt it to a human voice, but we wouldn’t sample back those vocal takes—we wouldn’t edit them. In certain songs it was a pretty hard job.

When you were recording parts in the studio, you were tracking individual instruments, right? You wouldn’t play live together in the studio?

There hasn’t been any live playing as a band, it’s only been [individual] tracking. Even the drums—when we were in the studio with Chris Zane, Igor played the drums individually and separately. He played the kick, then the snare, then the hi-hat, then the toms, and all that. We had some good surprises because most of the congas and stuff—there are a few tracks with congas—were the 707 congas, but Chris Zane, who’s very good at playing drums and percussion, re-recorded all of those congas, and re-recorded all of the percussion. Same with tambourines: all the tambourines we used were taken from the 707, but we re-recorded all of the tambourines, so you actually hear real tambourine. That was a pretty cool surprise.

With the last album, when you mixed it, it was a trans-Atlantic thing—you were in Spain and you mixed it remotely over iChat. Did you do it differently this time?

No, it was exactly the same. It’s actually a great way to work—you sit down in front of the computer, you open this stream link, and you hear what the mixer is doing in real time, and you can communicate on Skype or whatever. That gives you more time to do the tracking and to produce. You don’t really need to be in the studio because you’re hearing it in real time.

The way it works is that you can stream that mixing session. You send that link, you open it on iTunes, and you hear what’s coming from that person’s mixing board. Not all of the record was recorded here [in Barcelona]. We only did the tracking for guitars and basses, and some drum machines. We set all the MIDI files too, so that when we were actually recording it, in New York, we would only have to re-amp things instead of performing. But almost all the drums were performed by Igor—they were actually recorded there, and a couple of guitar lines were too. We used some of Chris’ synths too, because we had the MIDI files—so the bassline in “Spirit” was made with another sound, and we used another synth for that.

I noticed there is a reel-to-reel in the studio. Did you use that at all?

Oh yeah, the Revox. Some of the early demos had this reel-to-reel. We haven’t used it. We want to use it for mastering and stuff. It has this very cool thing we like: speed deviation. You can change the speed of the reel so that, instead of time-stretching things digitally, where there’s a loss of quality, you can time-stretch it analog with the Revox reel-to-reel tape recorder. We bought it because of that, and it’s always cool to send it through a tape machine in case you wanna give some crispness or warmth to the final mix. The speed variation thing is pretty amazing, it sounds very vivid.

There’s a Moog Prodigy in there too—did you use that much?

That’s like a museum piece for us. We never use the Prodigy, but that’s the first synth that we bought. We bought it back in 2002 or 2003, something like that. I haven’t plugged it in in years—we just wanna keep it.

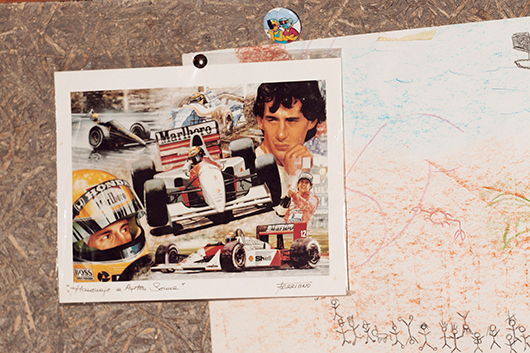

And there’s a picture of a racecar driver on the wall. Is that Ayrton Senna, whose name is the title of a Delorean EP from 2009?

Yeah! That’s Ayrton Senna.

Do you have a favorite piece of gear you used on this record?

There’s definitely this sound that I told you about: the M1 “silk guitar” preset. We modified that preset, but the name is “silk guitar.” That’s one of the features of the sound on this record. The Korg M1 sound has been used mainly for writing the songs, and the arrangements. For instance, “Dominion”—all of the song is based on the “silk guitar” sound.

I would personally say that I’m very happy with the way the guitars are sounding. We used to be Fender Twin Reverb people, but now we work more with sounds like the Roland Jazz Chorus 85 [guitar amp]. We re-amped everything at Chris’ studio with some other amps, but the chorus that this amp is giving you… is actually a chorus sound that we had in mind when we re-amped and produced the guitar sounds. So we actually recorded with other amps, but this guitar sound has always been in mind for us as a reference for guitars. There’s a lot of chorus on the guitars.

I’m pretty happy with the way the drums sounded too. Chris did an amazing job. [Our drums] have never sounded the way they sound on this record. There are a lot of gated reverb snares, for instance, which is another thing that shaped the sound.

You’ve described this as Delorean’s “big production album.” Could you tell me a little more about what you meant by that?

We basically got inspired by big albums from 1985 to 1990. We didn’t mean that this is like a “big production” record, because it’s been pretty cheap, but there’s been some effort in working in the studio in a proper way. A lot of inspiration comes from records from around that time, when there was a lot of money and the records that were put out were very taken care of. There was this hi-fi approach to songs, but it was still pretty much analog because computers were not there yet. Most of those records sound VERY big, they sound huge, and there’s this huge care in those records and it’s great. We had that in mind as an idea, as a reference, but it’s not that we think we made that—we only had it in mind.

Are you talking about pop records or R&B records?

I’m talking more like Peter Gabriel’s So, Paul Simon’s Graceland—huge studio efforts. A lot of records that are in that BBC Classic Albums series are a reference. Another album from later times is Primal Scream’s Screamadelica, a big studio album. Paul Simon and Peter Gabriel made so many records before Graceland and So, but with those records, they took their time and made big “studio” albums. They took like a year and all that effort and resources, and worked in the studio so much, and they sound the way they sound because of that.