Are the Days of the Mastering Engineer Numbered? Taking a Closer Look at LANDR

The premise of LANDR, from Montreal-based startup MixGenius, mirrors that of many other services in […]

The premise of LANDR, from Montreal-based startup MixGenius, mirrors that of many other services in our newly remodeled digital lives: remove the middleman and replace him with a host of multifaceted computer algorithms to do the job better, faster, and cheaper. LANDR is an attempt to apply this very model to the realm of music production—specifically, the mastering process.

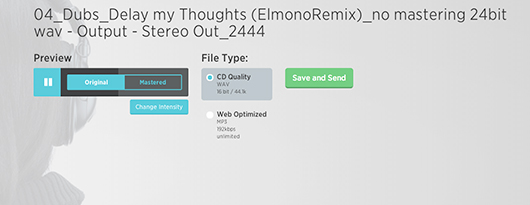

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given its scope, LANDR is the brainchild of a musician, a DSP researcher, and an astrophysicist. The heart of the company behind it, MixGenius, is its staff of roughly a dozen engineers. They’ve created what the company calls its “algorithmic digital mastering tool,” which uses machine learning to master music tracks without the need for a living, breathing mastering engineer. Users can upload their track, adjust the intensity of the mastering process, and within a few minutes listen to an A-B comparison of the original and the mastered track (and download it if the results are to their liking). For $9 a month, users get four uncompressed WAV masters; $19 a month brings unlimited WAV masters; 192 kbps MP3 files are free.

Without question, LANDR is the kind of technology that tends to ruffle feathers, but we wanted to examine how it actually performed. In practice, LANDR fared pretty well in mastering tracks we threw at it. The results were comparable and quite often better than applying a preset from iZotope’s Ozone plug-in (probably the most accessible and popular option out there for the untrained mastering engineer, starting at $250). It produced consistently solid, loud-without-being-slammed masters from a wide range of material, and did so immediately; the LANDR mastering process takes only as long as a track takes to upload to the site.

Where LANDR differs from the likes of Ozone and other software suites is in its ever-evolving nature. It’s designed as a self-learning engine, and gets smarter with every mix its users upload, and every choice they make. Currently, it takes just basic data from these interactions: whether a user likes the mastering job enough to download the resulting mastered file, for instance. But the breadth and detail of the data it’s able to parse from its userbase will continue to expand, and accordingly, there’s an engine update every two or three weeks to reflect what it has learned.

Many mastering engineers have a hard time explaining exactly what it is they do to tracks that get sent their way, alluding to a certain “feel” they get for the music at hand. If the same track is given to two different mastering engineers, two versions will come back that sound (at least subtly) different. LANDR, however, will send back the same track every time, precisely because it’s doing away with the human element. This is both LANDR’s guiding principle and the very reason why it’s unlikely to supplant mastering engineers altogether: mastering is equal parts art and science, and LANDR would appear far more capable of the latter than the former. Just as Instagram hasn’t replaced Photoshop, it’s unlikely that LANDR will replace the intimacy and knowledge of a highly skilled professional.

“Mastering engineers don’t bat 1000, and neither will LANDR,” says Thomas Sontag, head of communications and artist relations at MixGenius. (He also handles A&R duties at Montreal-based label Turbo Recordings.) “There’s a lot of complexity there, and what determines the best result is highly subjective. The beauty of LANDR is that everything is designed to come as close as possible to the psychoacoustic goal, and everything is built to improve based on the feedback and continued testing. There’s a feeling that the work we’re doing is building up a body of research and data that’s just going to improve.”

It’s a faith in the strength of the algorithm—especially its ability to learn and adapt—that serves as LANDR’s core competency. “If we grant that Siri is going to get better at helping with our lives and that these technologies really are the way of the future, well, we think that we can kind of run that space as far as mixing and mastering goes, and helping people finish their tracks,” continues Sontag. “We see loads of room for improvement. One of the things we’re working the most on right now is more granularity in the genre detection, so the system can more accurately decide on the overall mastering style.”

Indeed, there’s a psychological element to the cloud-based model as well. “That feeling of mystery is a big part of it,” says Sontag. “People don’t have the confidence and sense that they can properly master something themselves—and no offense to anyone, but that’s usually true. It’s really hard to do.” Sending the track off—even to a robot—and having it returned to you in better shape than it started fits nicely with the traditional workflow of producer and mastering engineer.

Somewhat similar to the way in which Shazam picks apart a song to identify it, LANDR uses big data and machine learning to understand what a track is and to process it, based on previously submitted tracks. Sontag imagines a not-so-distant future in which home producers upload the stems of a song they’ve made, select something along the lines of a preset for how they would like their record mixed (’60s psych, ’80s acid house), and let LANDR do the rest. While he won’t give a hard date for when a mixing-focused iteration of LANDR might be released, he says work on it has already begun.

“If we think big, and we think about the future, I like the idea of the legacy of [mastering house] The Exchange having their premium version of LANDR,” says Sontag. “I think there’s also interesting potential; people see LANDR as this total robot, but they don’t realize it’s actually kind of a hybrid. It’s not just a computer doing the thinking, it’s real human engineers working on this. In a lot of ways, it is mastering, just using a slightly different toolkit.”

It’s something he and the folks at MixGenius see as a solution to the current state of music production affairs. “When you consider how many people there are trying to make music now—the boom, specifically in electronic music—that when they take their little crack at it, that they have an option that makes them feel a little more confident about sharing that music with the world. I think that in the short term, LANDR is a mastering solution in line with certain realities of our time: we’re not just dealing with bands that spent a lot of money recording their album. We’re dealing with kids in their bedrooms, pumping out track after track. That’s the kind of era we’re living in.”