Interview: Dancefloor Thunderstorm’s Michael Tullberg

XLR8R speaks with the author about the history of Southern California rave culture and his visual documentation.

Southern California was on the ground floor when rave culture and dance music exploded in the 90’s and, thankfully, the archival tales and photographic relics of that time are now seeing the light of day. In a new book titled Dancefloor Thunderstorm—released in October of last year—electronic music photojournalist Michael Tullberg gives the reader a voyeuristic look at some of the biggest and most outrageous parties and underground raves from the 1990s and early 2000s. Reporting from the center of American rave culture during that time, Tullberg amassed an enormous library of photos, news articles, interviews, and memorabilia—the best of which make up the contents of his book. With hundreds of his tripped-out psychedelic images and insightful words, Dancefloor Thunderstorm takes the reader back on a blissful trip into the heart of the rave scene: From the warehouses to the after-hours clubs and deserts and mountains. XLR8R recently spoke with Michael in between shoots in Los Angeles to get a feel for where his journey started and where the culture took him.

When did you first come up with the concept for your book Dancefloor Thunderstorm?

I first got the idea for what would become Dancefloor Thunderstorm in the early 2000s. It was partly inspired by another book by Jonathan Fleming of Mixmag, titled What Kind Of House Party Is This?, which was his visual history of the original acid house explosion in England in the late ’80s. Having occupied basically the same role in the US as Jonathan had in the UK, I realized that I was in a good position to put something definitive about the Southern California rave culture era together. I felt a real sense of responsibility to show the world what this critically overlooked period of American culture was really like, especially given the almost universal negatively-slanted coverage of electronic music in the mainstream media.

In your book you mention a first, second, and third wave. Are you aware of any photography from first wave?

I know that there are a lot of photographs from that era floating around—you see more and more of them pop up on Facebook every day! However, I don’t know if there were photographers in the First Wave who were keeping comprehensive archives of their work like myself and other photographers did during the Second Wave. You have to remember that during those very early days, the rave scene was so below the radar that it wasn’t exactly attracting seasoned photographers like moths to a flame. The ones who were taking pictures at those events were the truly dedicated fans who’d caught onto it early on…and most of those, with respect, weren’t exactly professional shooters.

Mark Farina

What were your favorite ways of capturing moments using camera filters, settings, etc? What were some of your camera-gear highlights.

I had several camera and lighting techniques that I had either developed myself, or copied from other photographers who had preceded me. The point of this was to capture that amazing, fluttering, colorful, proto-psychedelic vibe that was so prevalent at raves. I started with high-speed films, and began using long exposures to re-create the fantastic energies that were ricocheting through the crowd. Then I started experimenting with multiple flashes, using colored gels to add to the rich ambient color already present at the gig. Another old flash-based trick I used was stroboscopics: the layering of visual layers via flash to illustrate movement.

Can you share some of your favorite experiences or most memorable artist encounters from those within the photos shared? We know about Dune, what else stands out in particular and why?

OK, I’ll share some memories from a few of these photos. Let’s see…

Paul Oakenfold, 1998

I shot this one at the Viper Room on the Sunset Strip. It’s of Paul Oakenfold, and this was the first time I’d actually had the chance to meet him and shoot him at length in an intimate setting. I’d encountered him before, but hadn’t had the opportunity to see how well we functioned together during a performance. As it turned out, Paul and I soon became friends, and we developed a very good on-stage rapport over the years—to the point where today it’s almost automatic. It’s a great feeling knowing that the electronic music equivalent of Eric Clapton or Jimmy Page is comfortable having you up there with him when he does his thing.

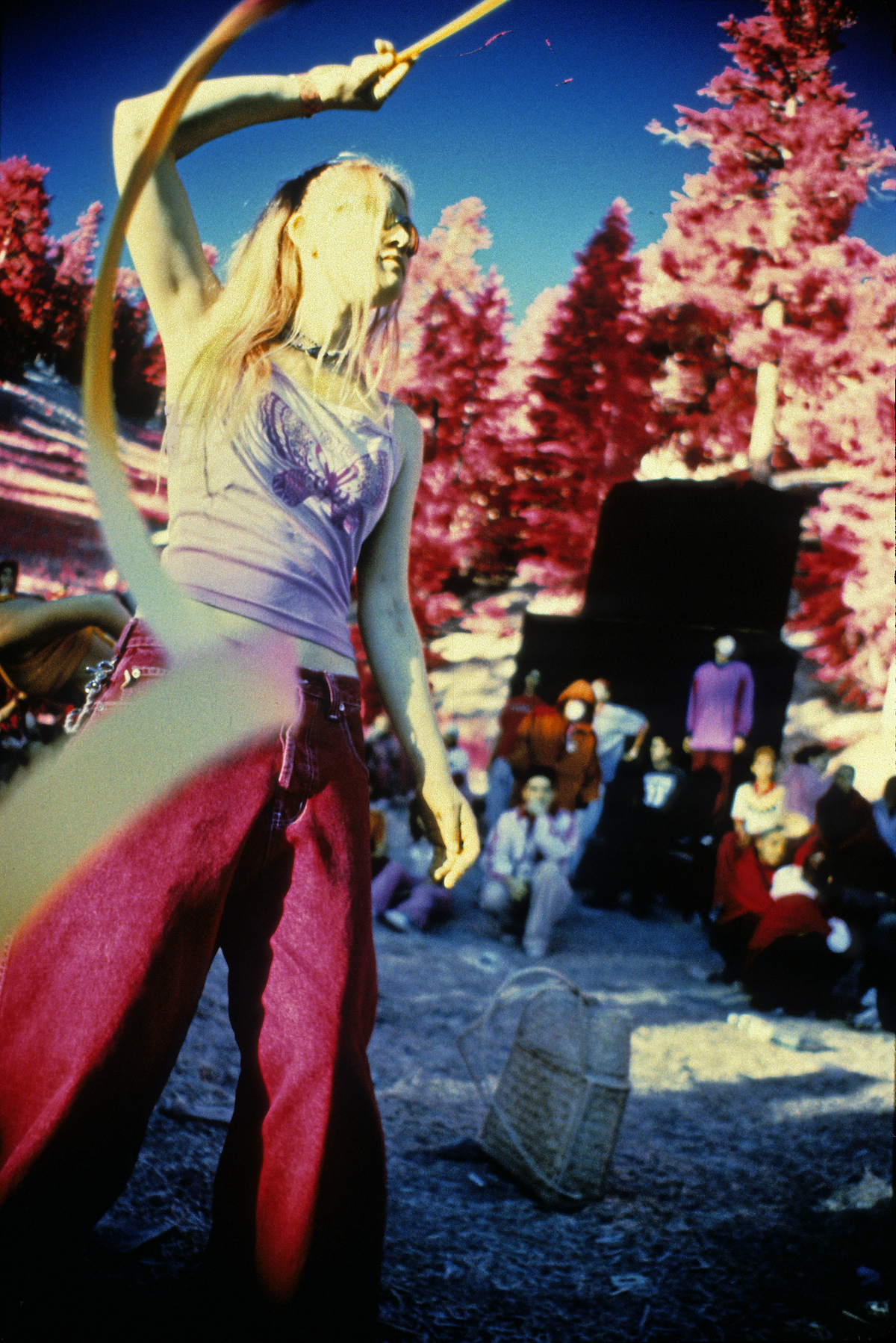

Mountain Girl, 1998

This is one of my favorite shots. It was created at a rave called “Midnight Sun” in August of 1998, in the mountains just north of LA. It’s 7AM or so in the morning and the sun is just starting to peek over the tree line. I purposely shot this with a very unusual film: Kodak EIR Color Infrared. This was a film that was originally designed in the 1940s for aerial surveillance, and later used by Jimi Hendrix for the album cover of Are You Experienced. It was one of my methods of illustrating the otherworldly vibe so often found at raves. The girl who was dancing here ended up being an extremely effective subject—for about ten seconds. After that, she was gone—and so was I, off to track down my next subject. That’s the nature of rave photography sometimes: the moments could be oh so brief, but also so rewarding.

DJ Sandra Collins, 1999

This shot came from one of the more hilarious nights out I had back in the day. Specifically, in February of 1999 when I got a call from my good friend DJ Sandra Collins. She said, “I’m spinning in Reseda in a few days, wanna come down?” I said sure, no problem. Anything to support a friend, right? So, fast-forward to the gig. I show up, and then Sandra shows up at about 11:30, to play at midnight. Since this was 1999 and Sandra was at the peak of her powers at the time, I knew this was very likely going to be a great set, and it was. There were only a few hundred or so people there, but musically they were happy as all-get-out…Sandra saw to that. That’s where the vibe for this multiple picture of her came from. Everything was firing on all cylinders—fantastic.

DJ Mars, 2001

This is DJ Mars at Electric Daisy Carnival, the 2001 edition. This was held at Hansen Dam in the Chatsworth area of the northern San Fernando Valley. Unlike the previous nocturnal editions of EDC, this was a full-on in your face daylight gig, in full view of the LAPD, the media, and the few in the mainstream who bothered to attend. Not only were there no arrests or incidents of any kind, the Southern California rave nation very clearly and unashamedly made its presence felt, as you can see in this shot. EDC had been big before, but this gig signaled the beginning of the transition from underground to above-the-radar for both the party and Insomniac.

How has your career and career goals changed through the course of documenting and being exposed to the underground rave scene?

My early career goals were directly influenced and fueled by the rave scene. It was the discovery of the rave scene that infused me with a huge dose of creative energy. I became immediately determined to not only document this incredible new social movement as best I could, but also to become the best photographer that I possibly could. So I basically inserted myself into the center of Southern California rave culture, which involved working for just about all the domestic dance-music mags of the day. This all served to eventually provide me with a good portfolio of top-notch material, which I used to parlay my way into Getty Images’ stable of entertainment photographers in 2004. My new goal became to get as much electronic-music-related events to Getty as I could. It wasn’t easy in the beginning; I remember when EDC was at the LA Coliseum, and Getty didn’t even know about it. Fortunately today, Getty has given a higher priority to electronic-music events, and I like to think that I had something to do with that.

Looking at the scene today, can you draw some parallels and point out some distinctions between the early underground rave scene you experienced and today’s EDM festival scene in the US?

Oh, I could go on for hours about this. Yes, there are parallels between the EDM generation and the original ravers. The music and the positive social aspects of the scene that surround it have always served as the basis for this whole thing, and that’s as true today as it was back in the 90s. The fact that the scene is not held in high regard by the mainstream media or most law enforcement is unfortunately a burden shared by both generations. And as far as general party atmosphere goes, that hasn’t changed all that much, whether you’re talking about a warehouse party, a club, or a stadium event—each has its own ambiance and identity, and time doesn’t really alter that all that much.

On the other hand, there are also great differences between the underground days and today’s corporate, commercialized festival circuit. One of the biggest of these is the relationship between the DJ and their audience, which Christopher Lawrence and I talk about in Dancefloor Thunderstorm. Something that we in the rave scene valued very highly was the fact that the DJ was in direct proximity to the people, very often playing on a card table, or on a barely elevated stage. The turntables were usually surrounded by a group of people who would watch, which meant that most of the audience couldn’t see the DJ at all. Thus, the focus wasn’t the DJ, but rather the music. Now look at a festival, where the headliners are seventy feet up in the air on a platform, physically isolated from the 60,000 people in front of them. How do they interact with the audience? The sad fact is that many of them don’t. I’m not going to name names, but just about all of us in this scene have seen one video or another where the DJ was pretending to tweak knobs, or not even bothering since their whole set was compiled beforehand. That’s presentation, not interaction. That’s something that the rave scene got away from, for the most part, and I miss that.

Thank you for contributing these beautiful and classic archival photos to this piece. These are all important bits of history when it comes to the US rave scene. Can you share any takeaways with us, something you’d like to emphasize about your work in Dancefloor Thunderstorm?

I have always felt that the time period of the rave scene is one of the most critically overlooked eras in American pop culture. I felt that way about it back then, and I feel the same way about it now. I genuinely believe that the rise of the rave scene and electronic music is the most significant cultural movement in American music and pop culture since the founding of hip-hop. I also believe it has been one of the most unfairly maligned music movements to come around in living memory, and that it deserves to be treated as part of the grand American music tradition just as much as jazz, swing, rock & roll, and the blues do. This is one reason why I wrote Dancefloor Thunderstorm—to give those people the attention and respect that they earned, one incredible party at a time. It’s time for those groundbreaking artists to receive the proper recognition they deserved but never got. It’s time for the stories to be told. This is our music, and it deserves to be celebrated.

You can find out more about Michael Tullberg by visiting him here. You can purchase your copy of Dancefloor Thunder directly by going here.