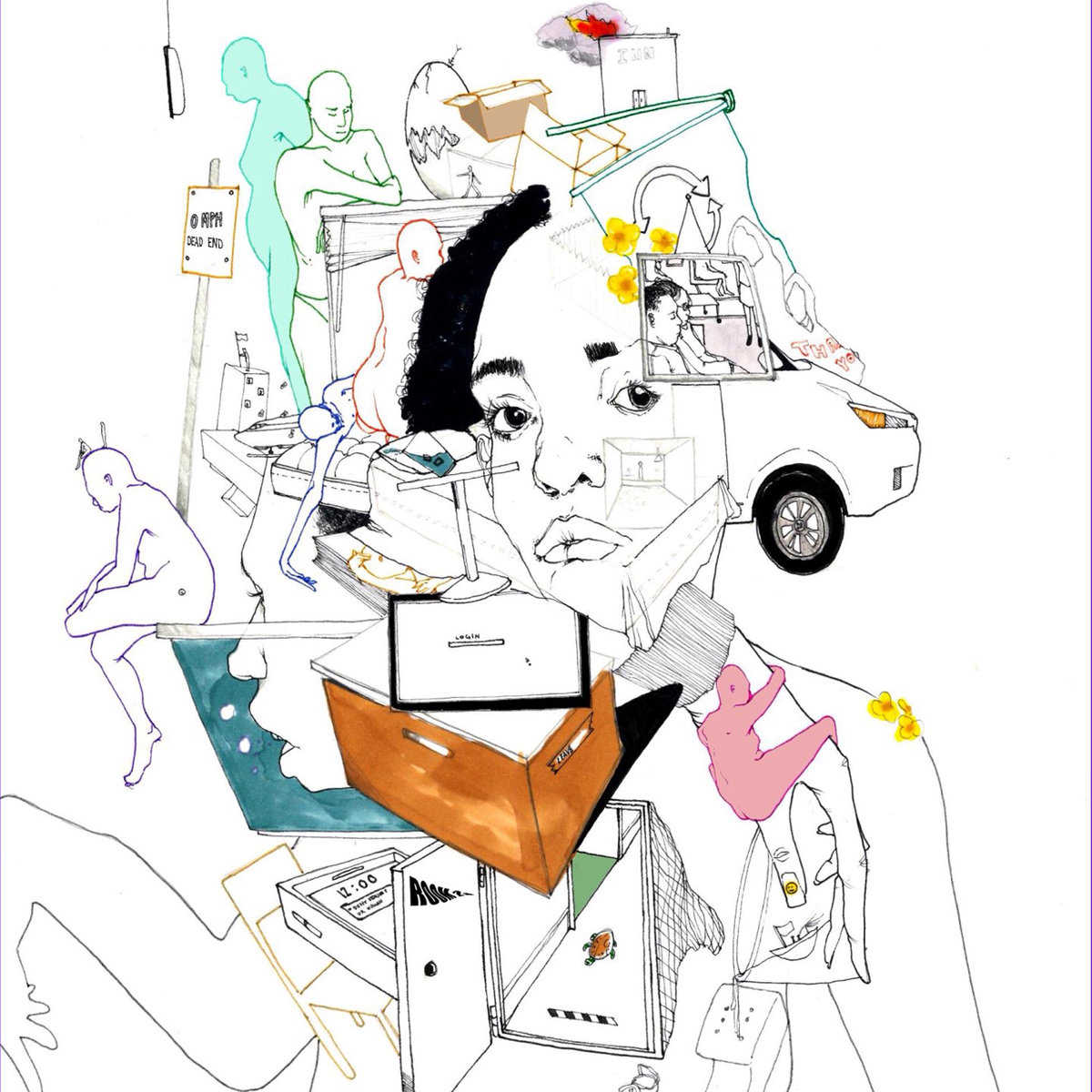

Noname ‘Room 25’

An impressive album debut from a rapidly maturing rapper.

Score: 7/10

It’s easy to think of any rap album released in the Donald Trump era as a document of political protest. Since 2016, records from Jpegmafia, Vince Staples, and Jay Z have felt like products of a divided nation. In Chicago however, a rich hip-hop scene has produced a number of emcees for whom America’s problems provide a backdrop rather than a focus. Artists like Fatima Warner (a.k.a. Noname) come across like young adults trying to live life— enjoy life even—while chaos unfolds around them.

Noname and other Chicagoans—artists like Jamila Woods, Saba, Ramaj Eroc, Valee—share a fondness for brightly coloured cadence, live-sounding instrumentals, and sing-song choruses. It’s a funk-inflected “acoustic hip-hop” sound traceable back to Chance the Rapper’s Acid Rap mixtape of 2013 (itself a modern reincarnation of Kanye’s early backpack rap) that has since been detectable in recent projects from Tyler, the Creator and the late Mac Miller.

After a brilliant guest verse on Acid Rap, Noname released the acclaimed Telefone mixtape in 2016. Her self-released first album, Room 25, shows an artist who has left Chicago (for LA), while largely remaining true to the musical norms established by contemporaries in her hometown. Like Chance, Noname doesn’t shy away from cultural commentary but is as likely to make nostalgic reference to Nickelodeon summer holidays as she is to critique Republican gun control policy.

As the distinction between mixtape and album continues to blur, it’s hard to decide how much progression to expect from Noname since Telefone, but the most obvious change is in the maturity of her own character. In a recent interview with Fader, Warner talks about not having had sex when she wrote Telefone, simply due to her own insecurities; by contrast, Room 25 opener “Self” presents almost Yeezy levels of cartoonish braggadocio, including the line “my pussy wrote a thesis on colonialism.”

Unlike Kanye though, Noname is immensely likeable, relatable even. “Realness” has become something of a holy grail in contemporary hip-hop, but it can’t be overstated quite how normal Noname seems to be, in everything from her NPR Tiny Desk Concert to the anti-fuckboy bars on “Window.” She even poses a retort to the relentless chauvinism of her male counterparts, intoning “You struggling to love yourself, believe me that’s karma,” shortly before admitting— almost apologetically—to not being a “nasty bitch.”

Before “Window,” Noname delivers two of her most ambitious tracks to date in “Blaxploitation” and “Prayer Song.” Over the funkiest bassline on the album, the first of the two is centred around three excerpts of dialogue from films of the 1970s, each of which acts as a chorus. Between them, Noname spits lightning-quick verses which question common perceptions of African American women: “keep the hot sauce in her purse and she be real, real blacky.” As well as a possible nod to Beyoncé’s “Formation,” the lyric critiques the kind of superficial stereotypes Hillary Clinton was guilty of in one of her vacuous campaign strategies.

Following “Blaxploitation,” Noname gives her take on police brutality with the impressive “Prayer Song.” The opening verse provides the most thrilling example of her knack for a beguiling rhyme scheme, channelling Busta Rhymes by bouncing similar syllables into one another. Delve deeper and you’ll hear a second verse told from the point of view of a racist cop, who gets an erection from violence and a bigger house from corruption. “I set my cell phone on the dash, could’ve sworn it’s a gun / I ain’t seen a toddler in the back after firing seven shots,” she spits, making direct reference to Jeronimo Yanez, the Minnesota policeman who was acquitted after shooting Philander Castile in 2016.

Noname’s quickness of tongue makes the album feel short and before you know it you’re into its second half. There’s a notable switch as the music becomes more hospitable and the lyrics less politically confrontational. With the exception of “Ace,” an annoying radio song with a chorus by Smino, the album’s back end is full of blissful production mostly credited to frequent collaborator Phoelix. Neo-soul jam “Montego Bay” offers the guest performance of the LP with Ravyn Lenae’s wonderful vocal, before the Thundercat-esque funk of “Part of Me.”

Those who like Noname’s more chilled efforts will appreciate the final two tracks on Room 25. The reverb-heavy guitar sample on “Without You” and piano on “no name” both recall Tyler’s use of Rex Orange County on Scum Fuck Flower Boy. Tyler and Noname are the latest in a line of rappers exploring the hollow, moody sounds made popular in the buildup to King Krule’s debut album, Six Feet Beneath the Moon (Kanye even approached the Londoner for a collaboration, but was unsuccessful.) Noname’s eponymous closer to Room 25 is wistful, soulful, mournful, and might make you wish there was a bit more to the album.

Although producer Phoelix excels in the album’s final moments, Noname is at her best when challenging herself in its first half. It can feel unfair to use Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly as a yardstick for every rap album since 2015, but the qualities it shares with Room 25—most notably the jazz inflections on tracks like “Self” and “Prayer Song”— expose some shortcomings in Noname’s latest effort. Nothing on Room 25 has the political power of “Alright” or the personal emotiveness of “u.” Interestingly, although Kendrick had been around a while longer, at 27 he was as old as Noname is now when he recorded his masterpiece.

Like Butterfly, Room 25 suggests an artist writing not simply about the challenges of being an African American, but about the nuances and inconsistencies of her own consciousness. With the lyrical talent she shows in places here, the more Noname challenges herself—the deeper she delves into her own mind—the more fascinating, stimulating, and thought-provoking her music will become. If “Prayer Song” and “Blaxploitation” are anything to go by, she could yet become a great rapper. For now, she’s a good one.

Room 25 is available now.